Sarah Bryant:

There comes a point in every artist's life when you realize that

just because you can, doesn't mean you should.

Sarah Bryant at the letterpress

When book artist Sarah Bryant first contacted me, I was ecstatic. She didn't know that I had been following her work for years and she was on my secret list of artists I want to work with.

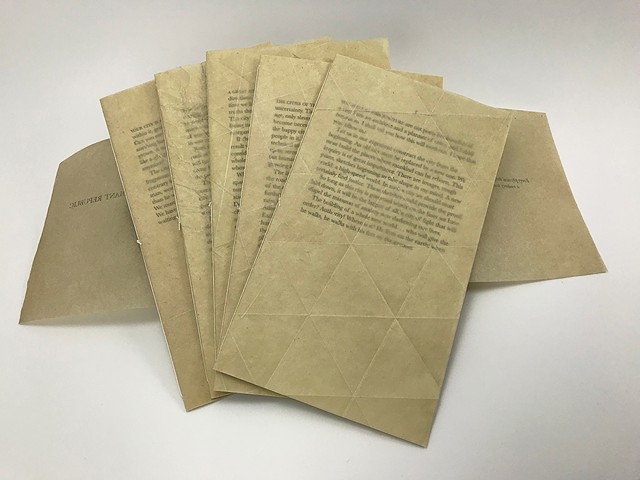

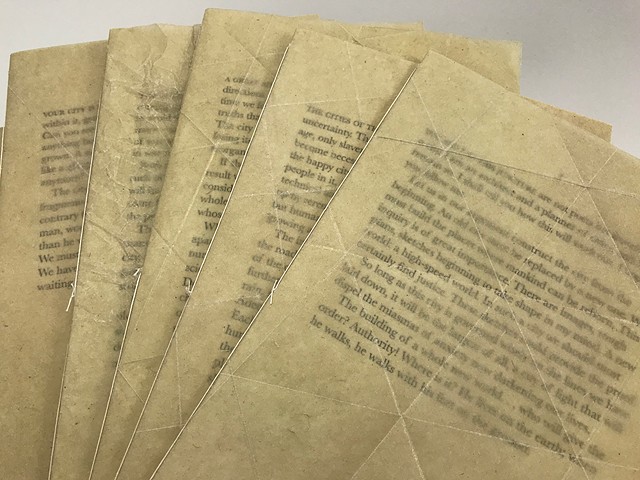

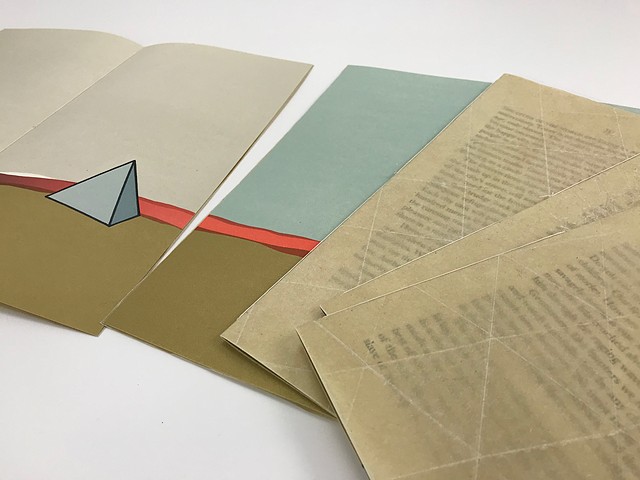

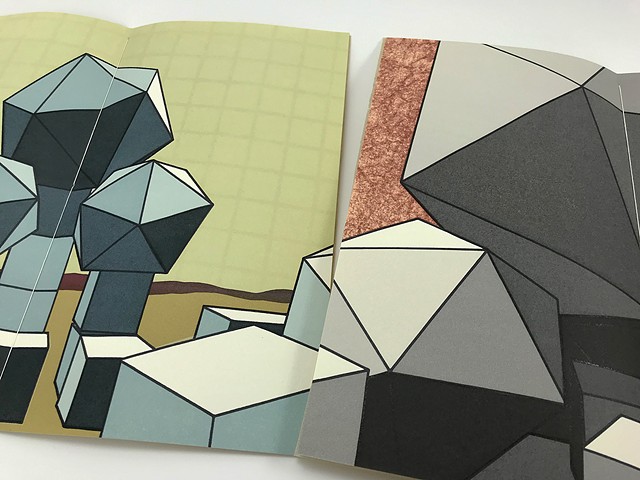

Her project was complex: it included five letterpress books printed on Handmade Belgian Flax paper with interlocking images and cast concrete shapes housed in a laser-cut box base (that’s where I come in!) with a printed Dubletta book cloth top.

Sarah was looking to collaborate with someone who could advise on materials and design, and bridge the gap between laser-cutting technology and the artist’s hand.

Step 1: Consultation

Our collaboration started with a phone consultation in which Sarah described her project, which called for 50 laser-cut boxes. Even when laser cutting is a piece of a much larger project, it's important for me to understand the project as a whole. Whether addressing conceptual concerns or physical construction, I can solve a problem more easily when I can see the big picture. In the case of Sarah's project, the box needed to be strong enough to hold several concrete shapes. Had I not understood this from the outset, we could have had some real problems down the line.

We talked about her different options both for the laser-cut box itself and for how much involvement she wanted to have in the laser-cutting process. Sure, that Sarah could have spent hours figuring out how to make a laser-ready file. But even better, she could save time by building a mock-up for this Sarah to use to create the laser-ready file for her. So that's what we decided to do.

Sarah’s mock-up (left) - Kerf tests (front) - Prototype (right)

Step 2: Mock Up

Part of the file-making process for laser cut boxes is figuring out the kerf, since the laser removes a certain amount of material when it cuts. I knew from experience that if I didn't compensate for this in the file for Sarah's prototype, the dovetail joints wouldn't be tight enough to hold the box together.

Because laser cutting is a heat-based method, and wood thickness and density can vary, figuring out the kerf can take several rounds of adjusting the file and testing. Once I got the right fit—snug, but not too snug—I cut the first prototype and sent it off to Sarah.

Production

Step 3: Prototype

Sarah had several things to figure out when she received the first proof. How did the design work with the other elements? Was the box strong enough to hold the concrete shapes? Did the design of the dovetails detract or enhance the piece? What was the most efficient way to glue the box together?

For Prototype #2 we adjusted the number of dovetails. Once Sarah confirmed that this didn't compromise the strength of the box, I went into production.

Ready for a bonfire

Step 4: Production

Production is pretty straightforward, right? The answer is yes, if you plan for it.

Anytime you are working with a natural material, such as wood, there will be variations that will affect the laser cutting. Expect to buy 5-10% more material than you think you need. For this project we were using Baltic birch plywood which, because of occasional hard spots, has areas that cannot be cut out fully.

To make 50 complete sets, I threw a few extra sheets into the materials order, to be on the safe side.

Conclusion

The Radiant Republic, built entirely out of language found in Plato’s Republic and Le Corbusier’s The Radiant City. In these texts, separated by more than two thousand years, Plato and Le Corbusier each describe a city plan designed to provide a framework for morality and ethics. These works are revered, but they are also deeply troubling.In The Radiant Republic, language from Plato and Le Corbusier has been combined to create a narrative in five parts. Each part is bound separately, and features a portion of an interlocking landscape with no fixed beginning or end. The project is housed in an elaborate enclosure featuring elements of wood, cement, and glass. Letterpress printed in an edition of 50 copies and completed in 2019.